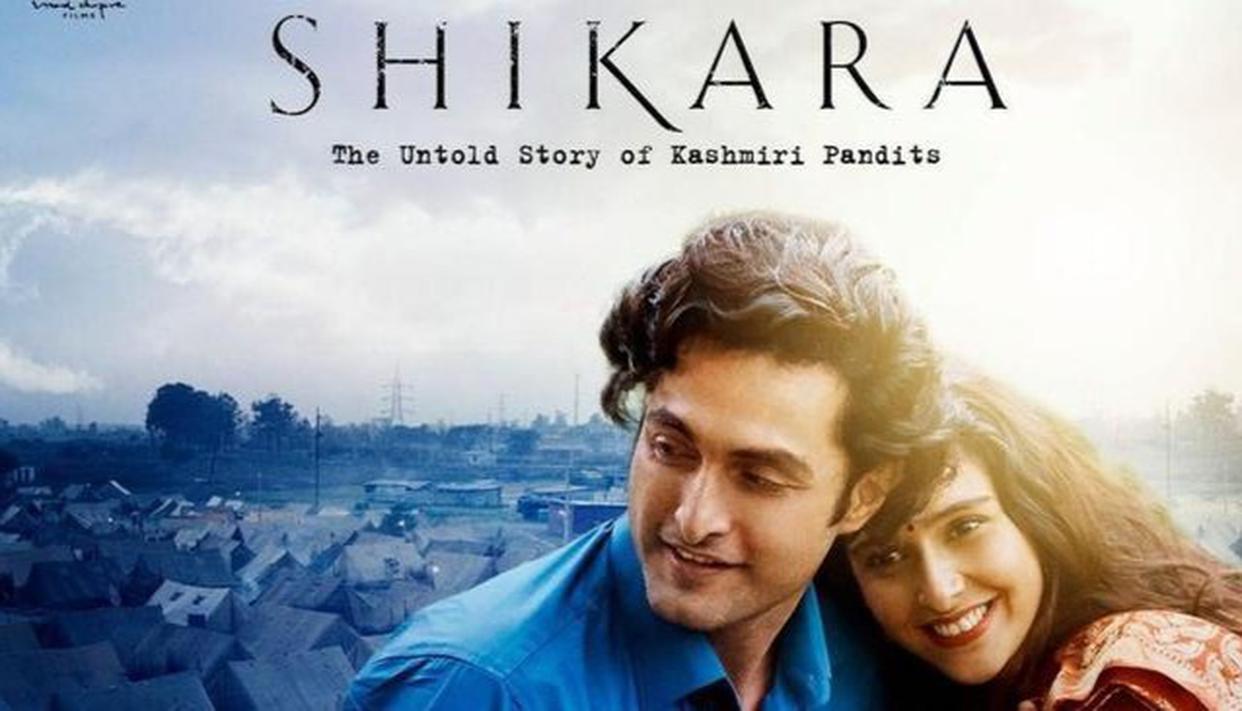

A film Shikara pDVDRip (2020) Full Movie can barely be separated from the time it is discharging in. Kashmir today holds the record for India’s — and seemingly the world’s — longest Internet shut down, with reports of human rights infringement in obscurity. Right now, mass migration of Kashmiri Pandits in 1990 is frequently utilized for political setting one human rights infringement in opposition to another.

Shikara pDVDRip (2020) Full Movie strolls this precarious landscape, where the effect of the film can’t be held in the limits of a film corridor. Maybe mindful of this, movie producer Vidhu Vinod Chopra contains the story to ‘individual’ experience, with loss of home, lives, personality and pride of a Kashmiri Pandit couple, conveying a flat, shortsighted and lukewarm blubbering, which in itself isn’t ignitable. Yet, Shikara pDVDRip (2020) Full Movie by peeling the story off of any political and chronicled setting, struggle or profundity, the film Shikara pDVDRip (2020) Full Movie remains at the peril of encouraging into an uneven viewpoint, in a previously polarizing time.

Shikara pDVDRip (2020) Full Movie

Executive: Vidhu Vinod Chopra

Cast: Aadil Khan, Sadia, Zain Durrani

Story line: Newly-marry Kashmiri Pandit couple, Shiv Kumar Dhar and Shanti, are driven away from their home and remain in a displaced person camp in Jammu

A producer is qualified for his point of view. What’s more, in doing as such, by concentrating on the misfortune and right around three-decade-long unfulfilled want for one’s country, Chopra focuses on feelings instead of governmental issues. Shikara Full Movie makes no endeavor to talk about what disturbed the appearing amicability, adding the same old thing to the discussion. In a beautifully depicted Kashmir, clamoring with a one of a kind culture, the film endeavors to bring out the departure of a heaven that was, as the story starts in 1987. The hero, Shiv Kumar Dhar (Aadil Khan) weds Shanti (Sadia) in a conventional Kashmiri wedding.

His energized Muslim closest companion Latif (Zain Durrani), whose father enables the youthful couple to construct their house, is an essential piece of their lives. The demise of Latif’s dad in an assault pushes him to militancy. While the film credits Muslim aggressor radicalism to individual misfortune, the ethical high ground is consistently with Kashmiri Pandits. For example, several years after the departure in 1992, Shiv tenderly adjusts a couple of children reciting, ‘mandir yahi banayenge’, by disclosing to them that a decent pioneer joins together, not isolates. In any case, a go getter Muslim neighbor back in the Valley has hunched down Shiv’s home on the guise of guarding it and painted the insides all green.

During the mass migration, as Pandits are driven away from home, the recollections of injury are joined by serenades of ‘azaadi’ in Kashmir, and in one scene, previous Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, on TV, shows her solidarity with Kashmiri Muslims. In its pale account, in this manner, what stands apart are minutes like these, which is an update that a film can’t cover the legislative issues of a story under the clothing of ‘affection and expectation’. Past the ‘great Hindu, great Muslim and awful Muslim’ figure of speech, the discussion created by the film is of denied equity by progressive Indian governments and lost culture as the recollections of Kashmiri Pandits start to melt away.

The interest is for the 4 lakh Kashmiri Pandits to come back to the Valley, and Shiv composes 1664 letters throughout the decades to the Presidents of America, to look for universal solidarity. The letters fall on hard of hearing years, which is suggestive of the harsh truth that, independent of time and religion, the contention in the Valley is constantly an ‘interior issue’.