Watch Online / Download Every Breath You Take 2021 Full Movie Free

In the tediously unsurprising 1990s legacy circle that Every Breath You Take possesses, the mix of an easily upper working-class family exploring a difficult time while living in innovator land pornography constantly implies they will fix their frayed bonds by pummeling around that house battling for their lives against a seething crazy in the last reel. Particularly when there’s an outsider with a fresh English intonation and cut-glass cheekbones included, went with consistently by a worrisome string score. Past its overqualified cast and the eyebrow-raising plot focuses, this walker mental retribution spine chiller offers not many shocks.

The content by David K. Murray has been kicking around since 2012 when it was first declared as a Rob Reiner project promoted as being in the Cape Fear form. Harrison Ford and Zac Efron at first were in converses with star, yet the current cast met up in fall 2019, with New Zealand chief Christine Jeffs appended around then. She exited before long and was supplanted by Vaughn Stein (Terminal, Inheritance). The first title was You Belong to Me, which proposes the makers have been examining Police verses for a snappy expression, paying little heed to its significance to the invented story. A preface shows gushing mother Grace (Michelle Monaghan) driving her adolescent child Evan (Brenden Sunderland) to ice hockey practice one night when they are caught unaware at a crossing point by another vehicle and the kid is slaughtered.

An unknown timeframe later, Grace works through her pain by swimming fiery laps in the pool of their smooth Pacific Northwest home. Her better half Philip (Casey Affleck) has hurled himself entirely into his work as a specialist on the workforce of a neighborhood psychiatry organization. Their enduring adolescent little girl Lucy (India Eisley) has been kicked out of an all-inclusive school after being found grunting coke. It turns out to be certain that every relative has withdrawn into their own private torment, with correspondence and enthusiastic help lost en route.

A look into one of Philip’s meetings with his patient Daphne (Emily Alyn Lind) uncovers her to be a delicate case, with a background marked by psychosis in her family, various self-destruction endeavors, and an oppressive beau whom she seems to have traded for an unfortunate obsession with her therapist. In any case, Philip considers her to be a victory of strange strategy. Giving the patient a bogus name, he reveals in a school address that he broke with the standard methodology by sharing his own injury and different subtleties of his own existence with her, permitting her to feel less alone.

Months after the fact, she’s off her medications and working a book about her excursion out of the darkness. Faculty dignitary Dr. Vanessa Fanning (Veronica Ferres) is European, so she knows better. She’s worried about Philip’s expert lack of regard, reasonably so given that lone a Dumbass Movie Therapist would endeavor such treatment with an obviously temperamental patient. However, Philip excuses Vanessa’s concerns as “old-school.” Soon after, he gets a terrifying call from Daphne, whose closest companion has been slaughtered in a quick in and out mishap. He organizes to see her the following day yet she passes on that very evening in clear self-destruction, leaving her English-instructed sibling James (Sam Claflin) distressed.

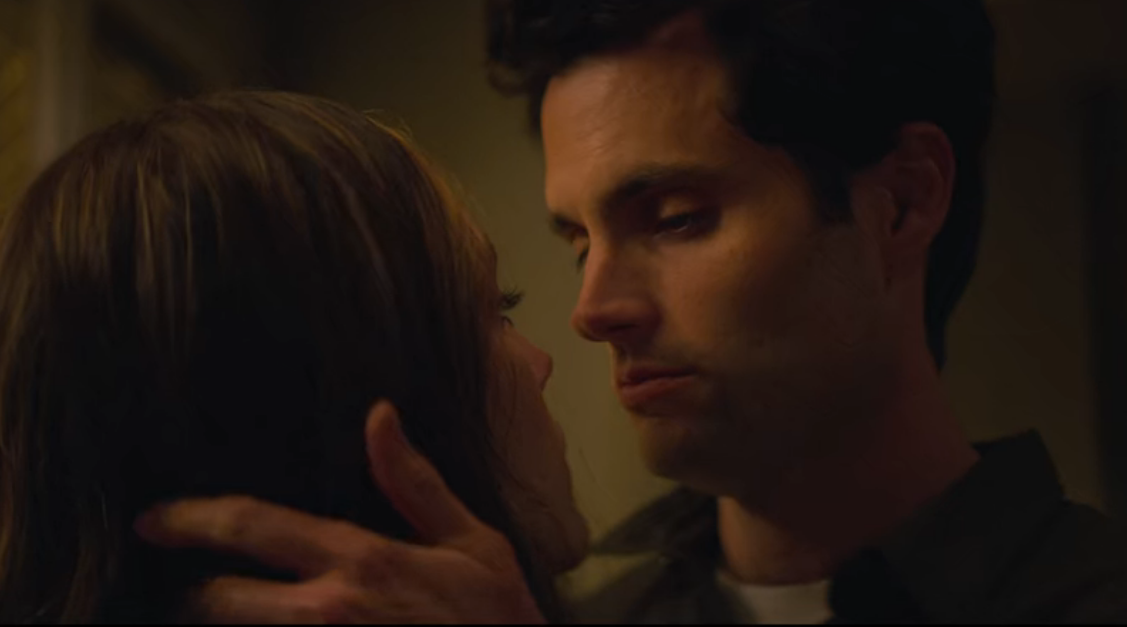

At the point when James appears at Philip’s home to return a book Daphne had acquired, Grace welcomes him to remain for supper while gloomy Lucy breaks character by shooting fainting looks across the table. “Family’s everything that matters,” James tells Philip in a code-orange admonition sign. “What’s more, you have an extraordinary one.”Anybody with simple information on by-the-numbers psycho-thrill rides will see the bristly course James’ communication with the family is going when he begins tenderly romancing Lucy while joining land merchant Grace to deal with the offer of his dead sister’s palatial house. “The most profound hurt I’ve at any point felt was the point at which I attempted to do great and was disgraced for it,” says James, citing Daphne in a line that doesn’t bode well even all things considered.

Claflin turns on the frosty appeal viably enough, with Philip getting on adequately ahead of schedule to figure that James is behind the protest letters disparaging him with the workforce and the Washington State Board of Psychiatry. The harm delivered on his family by long stretches of quiet and natural misery gives James a route in, also close to home information he’s gathered from Daphne’s point-by-point compositions. A frightening panic uncovers his brutal expectations, yet Murray’s screenplay holds fast to the recipe by having everyone unwind too early before hitting them with an unavoidable turn and releasing the last round of horrible discipline.

Stein puts a workmanlike stamp on the material with minimal perceptible style, however, DP Michael Merriman, at any rate, carries some visual grouchiness to the numerous night scenes of vehicles winding along roads through thick forests. (Area shooting occurred in Vancouver.) The film makes unclear gestures to the destructive impacts of loss left untended, however, this is fundamentally reflexive mash, gently classed up by nice entertainers.

The continually convincing Monaghan specifically approaches now and again to make an influencing character, however, Affleck won’t be numerous actually a for people particular clinical scholastic, less and less so with every shaky choice Philip makes. In “Every Breath You Take,” Casey Affleck plays a specialist — or more forthright, he plays a film therapist, the kind of character who’s been around since Ingrid Bergman looked through wire-rimmed scenes, offering subdued pensées about suppression in Hitchcock’s “Enchanted” (1945). The film therapist may, now and again, bear a passing likeness to the genuine article, however generally he’s an animal unto himself: perfectly dry and disengaged, jotting extraordinary gobs of notes and — definitely — managing his very own mystery closetful issues.

Affleck, who frequently plays calm men with a short wire, here dials back the secret unpredictability, embracing an insightful quality of peacefulness that he wears shockingly well. Attractive in trim facial hair growth and fashioner glasses, his voice tuned to a note of pacified compassion, he persuades us that Dr. Philip Clark, an advisor who works out of his home in the Pacific Northwest, is definitely not a miscreant, yet that he has wrecked his life barely enough to merit a just reward. Or if nothing else a significant revision.

The just reward shows up as Sam Claflin, a British entertainer who has regularly played heartbreakers, here cast as a charmingly “true” and suggesting creep who makes it his main goal to upset the great specialist’s life. Why? One of Philip’s patients, a young lady named Daphne (Emily Alyn Lind), went through 14 months in a psych ward and continued undermining self-destruction. So Philip chose to help her out in a most strange manner. In his beautiful office cave, he wriggled past her protections by dropping his therapist façade and revealing to her his biography, including things he’d never told his better half. He shared his injury.

It worked: Her self-destructive considerations retreated, her bothered indications disappeared. We see Philip examining the case, with a bit of pride, before a crowd of people at the school where he instructs. And afterward? At that point, Daphne’s companion kicks the bucket, and she’s troubled to such an extent that she takes her own life in any case. So much for a minister of treatment making himself a questioner.

James Flagg (Claflin) is Daphne’s lamenting sibling, who after moving beyond the stun of her demise introduces himself as an amenable and thoughtful chap. Yet, we would already be able to see that it’s a demonstration since he burns through no time moving into the existences of Philip’s realtor spouse, Grace (Michelle Monaghan), and his little girl, Lucy (India Eisley), a pained young person who is home after getting kicked out of all-inclusive school for doing a line of cocaine in a science lab. She’s ready for a tasteful terrible kid like James. The arrangement is a knockoff of “Cape Fear”: rotten one with resentment — possibly a supported one — stalks the object of his disdain by attempting to destroy his family. His most undermining instrument? Temptation.

Claflin is a marvelous entertainer who, at minutes, has helped me to remember Hugh Grant. Here, with a dignified way this side of agonizing, giving those perplexing dimples an exercise, he’s more slithery, similar to Matt Dillon implanted with the sneer of John Lydon. His James is a conceived controller who’s infuriatingly quite thoughtful. Until he isn’t.

![Every Breath You Take Ending Explained [SPOILER!] | Cooncel](https://i0.wp.com/cooncel.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Every-Breath-You-Take-scaled.jpg?fit=2560%2C1440&ssl=1)

“Every Breath You Take” was shot in Vancouver (subbing for rural Washington State), and the two houses wherein a large part of the activity unfurls are such elegantly excellent bits of land pornography, so disconnected against their cloudy snow-covered mountain backgrounds, that they could nearly be country manors out of a Jane Austen epic. The film is by all accounts occurring in The Wooded Land Of No Neighbors Or Streets With Stores.

You get the inclination that the chief, Vaughn Stein, got fixated on the plan of the thing: the phony chimneys that look more extravagant than genuine ones, the innovator wine glasses, the historical center like coffeehouses, the Clarks’ wonderfully long and slender pool, which Grace appears to take a spirit purging dunk in every other scene. There isn’t a shading in the film that isn’t dim, white, green, dark, or earthy colored, all lit by perfectly cloudy skies.

You just wish that this much consideration had been pampered on the content, by David K. Murray, which is utilitarian and, at critical minutes, rather negligible. The film conveys you along, and it has some high-strain minutes, however, there are such a large number of unintentional running-into-one another around close experiences (James has a method of springing up like a slasher). What’s more, the film holdbacks on the nuts and bolts of what ought to have been a focal issue: Why did Philip choose, so carelessly, to spill his guts to his patient? He gets shown who’s boss for it, and we can reason, in the theoretical.